MAURICE

(1971-1951)

British major-general Sir Frederick Barton Maurice wrote an essay on the size of Xerxes' army following his field work and reconaissance of the terrain in the Chersonese, the part of the march after Xerxes crossed the Hellespont. It is not indispensable to read his paper to understand this page, but it is a good read, with plenty of useful detail, apart from the conclusions I disagree with (Maurice, 1930). His paper refers specifically to the segment of Xerxes' march from Abidos in northern Anatolia, to Doriscus in Thrace. He even gives an update for the location of the pontoon bridges over the Hellespont.

Maurice bases his rejection of Herodotus numbers on historical habit, branding them as impossible from the get-go, and before he gives explanations and arguments for the number he arrives at. The reasons to discount an army larger than his number, 210,000, fall into three categories, water supply, terrain difficulty, and camp size requirements.

LOCATION OF THE BRIDGES

The location of the bridges plays no part in Maurice reckoning of the size of the army, but it is an important argument that illustrates Maurice's thinking. To invaded Greece Xerxes builds two pairs of pontoon bridges over the Hellespont, to cross to Europe; the first pair fails to withstand a storm and is lost. A second effort results in the completion of two new bridges, which this time remain in place and serve their purpose. One bridge is earmarked for combatants and the other for the baggage train. To support the bridges Xerses uses hundreds of warships facing the current, fastened to anchors, each other and the shores.

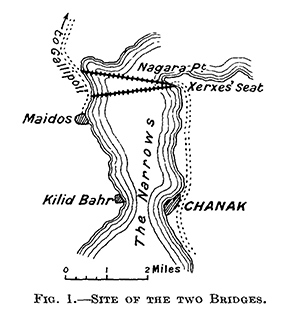

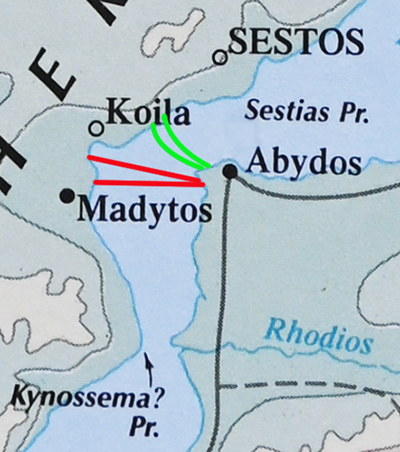

Herodotus says that the bridges crossed from Abydos (modern Nara Burnu, Turkey) to the European coast, between Sestos and Madytos.

NAMES OF CITIES AND PLACES IN THE MAPS

| ANCIENT NAME | BRITISH NAME | MODERN NAME |

|---|---|---|

| Abidos | Nagara Pt. | Nara Burnu, Turkey |

| Sultaniye Kalesi (medieval) | Chanak | Çanakkale, Turkey |

| Madytos | Maidos | Eceabat, Turkey |

| Sestos | (near) Bigali Kalesi, Turkey |

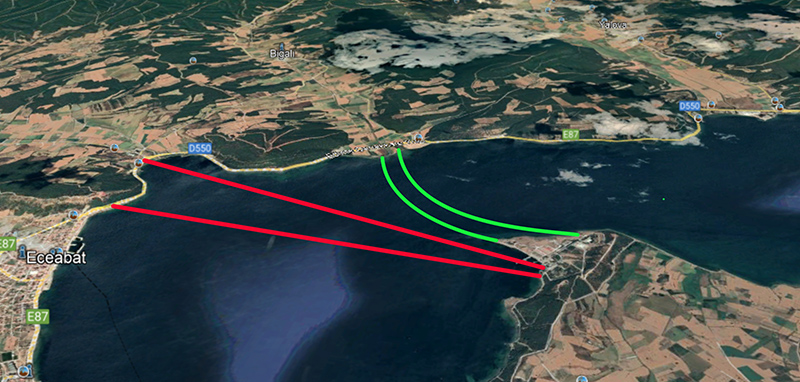

Maurice's Bridges

The figures below show a probable location of the bridges (in green) and Maurice's bridges (in red) according to his theory.

Probable Locations

Maurice places his bridges on the European side still between Sestos and Madytos, as per Herodotus, but the main difficulty of his argument is that his bridges are twice as long as needed in an effor to reconcile the number of ships used on each bridge and the bridges' lengths. A shorter crossing (in green) would have been much prefered, as twice the length is at surely twice the cost and effort and many times more technical difficulty over a longer span. That would aggravate a project already pushing Persian capabilities past comfort. Maurice also needs to leave 4.87 m (16 ft) between ships, which seems excessive, to make his numbers work. Herodotus does not explain why the northern bridge had 460 ships and southern bridge only 414, but there are several plausible explanations. Engineers had to find the right interval between ships, to offer not too strong a barrier to the current and yet provide sufficient support. Maurice assumes that more ships meant more length, but that is not necessarily so. More ships can mean also that the northern bridge required more support for the intended use, as it would be the case for the baggage train bridge, used by heavy carts, wagons and draught animals as well as people. We simply can't know either how much the shores have changed in 2500 years, when we use modern distances. It's merely futile, therefore, to engage in the kind of calculation Maurice presents, pretending that it yields reliable information. To realize how modern distances may not be a great reference, note that Herodotus says that the shortest distance between Abydos and the opposit shore was seven stadia (), that distance today is (), Maurice's argument seems to be that they had to build longer bridges in order to use all the ships available.

Surely not all ships devoted to a bridge were part of its final length. There would have been side attachments to the ships, cables sustained over ships from a strong point in the bridge to a land bollard, a series of them along the bank to provide a lateral attachment for the bridge. Perhaps several such per side of the bridge on both shores. A number of ships would have been devoted to this ancillary role. Other precautions would have been to use anchor ships between the heavy anchors sank at the bottom of the strait, to the bridge, so that the anchor cable would not damage the bridge but the middle ship. Anchor ships would have been all along both sides of the bridge, for while the current was alwasys in one direction, the wind could change inpredictably. This or similar precautions to add strength and stability to the bridges are made the more plausible considering the position of the overseers. The executive team that lost their heads soon after they lost the King's bridges, too feeble for the mighty Hellespont. These were men acutely concentrated on doing a good job. (See Hellespont).

The top-down view of the attachment to shore of one bridge, and its anchoring further into the stream. Xerxes bridges had to contend with powerful changing winds and the water current. Facing the current, slim triremes, having no keel, appear to be a low drag proposition floating in the current.

Figure 2. -- Bridge detail on ancient map.

In reality, Persian engineers had to strike a balance between the competing needs of providing enough support for the bridge (more ships, more support) and to offer the least resistance to the current and winds (the fewer ships, the less drag), which must take a few trials. Then had to find suitable lanward sites, and build the shortest bridge between them. This makes Maurice's theory for longer bridges quite implausible.

Let us check Herodotus numbers: The beam of a trireme is given at 5.48 m (18 ft) which makes it impossible to fit 460 or 414 triremes side-by-side in 7 stades (1,295 m / 1416 yd). Thus, the bridges did not follow the shorter line between shores, or a good number of them were used for ancillary functions, but were not part of the length of the bridge, or both.

Herodotus gives the shortest crossing from Abydos to the opposite shore as 1,295 m (1,416 yd). It is impossible to fit the number of triremes quoted for each bridge in that distance. Side-by-side, 460 triremes would occupy, 2,520 m (2,756 yd), and 414 triremes, 2,268 m (2,480 yd).

If we trust Herodotus, then there should be obvious explanations for those impossible numbers. Maurice chose to make the bridges longer to accomodate all those ships in their length. But there are other ways. I don't believe Xerxes builders would choose to make a longer bridge unless there was an imperative reason. I can't see one. Maurice mentions that his location has more favorable currents, but the twist the course the wather has just been through should actually make for extra disturbance in precisely spot Maurice's bridges lie, and that the minimal distance across the strait at that point was seven stades; that is, The length of the bridges would have been longer due to their curvature, which could add 10-20% length depending on the depth of the curve. Each bridge had a width of some 10 m (32.8 ft)

The green bridges in the figure below, cross the shortest distance between Abydos and the opposite shore, 1968 m (1.22 mi), and appear logically correct. The bridges, however, would have extra length due to the arc shape caused by the force of the current. The length of the green bridges, therefore, would be around 2.3 km (1.42 mi), while the lengths of Maurice's red bridges are almost double at, 4.31 km (2.68 mi) and 4.21 km (2.62 mi), respectively, as straight lines.

Figure 3. -- Bridge detail on Google Earth.

CAMP SIZE REQUIREMENTS

TERRAIN DIFFICULTY

I then came to the conclusion that the nature of the country put a definite limit upon the size of an army marching under such conditions as Herodotus describes (p. 210). See: march description

WATER SUPPLY

Water supply is the biggest reason for Maurice's conclusions on army size. Unfortunately, they are based on incorrect calculations and assumptions and need to be set aside. For example:

Maurice claims: A river, unlike a reservoir, cannot be drained to the last drop, and its water is flowing away while it is being drawn upon. Therefore not more than about one-third of its total content can be made available, without arrangement for storage, for watering an army at any given time.

This was patently not true for folks who had inherited the Assyrian and Babylonian empires, where large scale agriculture in the drier parts had depended for millennia on the digging of canals. There were numerous expert canal diggers in the Achaemenid empire. The Colchians (modern Georgia) are said to have been canal specialists, as were the Egyptians and the folks in the flood plains of the Euphrates and Tigris. The point was to divert the river dry if it need be, into canals for either irrigation or the watering of beasts and men. In fact, the Scamander river, does this process naturally, the current peters out into marshland before reaching the sea. Xerxes could have done the same upriver using canals to water his army.

There are many springs, rivers and lakes along the itinerary of the march, but fewer in the Gallipolli peninsula. Maurice's less than comprehensive river survey, centers on the inadequacy of the Scamander and Melas rivers. Maurice on the Scamander river (modern Karamenderes):

The Scamander was the last large source of water supply available for the army before the Hebrus was reached, and by use of a formula, commonly used in military reconnaissance to estimate water supply, which gives sufficiently accurate results for practical purposes, I calculated that the flow of the river in October 1922 was in its lower reaches at the rate approximately of 50,000 gallons an hour (p.221).

This seems incorrect on two counts. First, Maurice visited the region in October, and Xerxes in April when water would be plentiful in the spring before the dry season. The dry season is in summer, not in April. Secondly, the flow of the Scamander varies considerable, but this is its total annual discharge:

The ancient name of the river is Scamender. The river arises from Ağı and Ida Mountains and run through ancient Troy city and flows into Çanakkale Strait. Its annual water potential is about 460 hm3(Kale, 2018)

A cubic hectometer contains a billion liters (264,172,176 gal). 460 hmi translate to an average discharge of of 14.5 cubic. That is, 52,000,00 (13,789,787 gal/h) per hour. Climate change and agricultural irrigation have reduced the flow of this river to 0.9 m3 at times. That low flow rate still carries 3,240,000 liters per hour (856,000 gal/h). It is obvious that Maurice's discharge of 50,000 gal/h, must be incorrect by several orders of magnitude. Despite this amount of water, this river failed to meet the demand and other unspecified measures needed to be taken. Mount Ida, called by Homer "many-fountain" (πολυπίδαξ), sourced several rivers, including Rhesos, Heptaporos, Caresus, Rhodios, Granicus (Granikos), Aesepus, Skamandros and Simoeis

Herodotus mentions rivers and lakes drunk dry along the way, as insufficient to cope with the water demand; the situations were obviously handled without loss of life worth mentioning. Maurice underestimates the Quartermater a little bit; any dry spot in the Chersonese or elsewhere would not have come as a surprise. Same as food depots were placed strategically along the itinerary, the same situation would have obtained with water. Never underestimate the bandwith of a caravan of mule carts hurtling down the way track loaded with tons of food and yes, water. Messenger horseriders would move like quicksilver to and from the guides leading the marching army and the camps and depots ahead next, to signal the army's approach and start the filling of canals and preparation to dispense victuals and replenish the baggage train.

Çanakkale strait near the ancient city of Troy. The river is about 110 km in length and has minimum and maximum flows of 60-70 m3 and 1530 m3, respectively (Baba et al., 2007; Sarı et al., 2006).

THE GOOD PARTS

I am most happy that Maurice's paper contains ideas very much along mine in important aspects of Xerxes' March.

- Combatants and baggage train proceeded on parallel tracks. Supplies and attendants close by to feed the troops. This is the singmost important feature that allowed the Quartermaster to greatly simplify the distribution of food and supplies, and the (march configuration). It was expensive but scalable. In ancient military expeditions, the baggage train usually followed the combatants, which would not have worked in a march stretching hundreds of kilometers, the Persian Quartermaster kept the supplies chugging along with the troops.

- The march could have included several prongs, one of which included the royal cortege.