Hellespont is the ancient name for the Strait of Dardanelles, the channel of water of some 65 km (40.3 mi) connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara, which together with the Bosphorous comprises the Turkish Straits System (TSS).

Pindar and Aeschylus note the Hellespont was named after a girl named Helle. Together with her brother Phrixus, she was about to be killed as a human sacrifice, but they were miraculously rescued by a ram with a golden fleece, which flew them from Greece to the north. Unfortunately, Helle fell into the sea, which was called after her: Sea of Helle.

Maps

The maps in Figure. 1, show the location of the Hellespont at the meeting point between Europe and Asia. The lower map closes up on the location of the bridges Herodotus describes, and the shortest crossing in that area. It shows also the even narrower crossing a few kilometers south, at Çanakkale, which Xerxes' engineers did not choose as crossing point. It was probabably not as narrow 2,500 years ago, because the silting action of a substantial river (ancient Rhodios) has narrowed the distance. The Strait overall has widened over time. Herodotus says that the shortest distance from Abydos to the opposite seashore was seven stadia, 1.3 km (0.8 mi). Today, the shortest crossing at the same location is 66% wider than in Herodotus' days, at 1.96 km (1.22 mi).

Maps feature modern names with ancient names overlaid in red text.

Figure 1 -- Hellespont crossings detail.

Herodotus has the two bridges spanning from Abydos to landing sites in the opposite shore between ancient Madytos and Sestos. The landward points of the shorterst crossing seem to have adequate areas for the transient army, as shown in Figure 2.

Obstacle To Conquerors

Persians, Macedonians, and Romans at war, to name a few, had to cross this formidable obstacle in their way to conquest. Most armies were ferried between continents, but not Xerxes' army. His navy supported bridges instead. The prevalent conditions make the construction of the pontoon bridges Herodotus describes an almost miraculous feat of engineering.

The Hellespont is difficult to navigate; perhaps not as difficult as the Strait of Magellan, where maritime piloting is compulsory, but not far behind. Hellespont water flows in two directions in an exchange of buoyancy between the two seas: low salinity water imported as a surface flow from the Black Sea to the North Aegean, and a subsurface, highly saline layer of Mediterranean water exported from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea (Kokkini, 2014). Water streams sharing the same channel in this manner causes surface turbulence, an when added to the twists and turns of the Strait and a bed of varying dept, 55 m (60 yd) average and a maximum depth of 103 m (112 yd), it makes for challenging navigation.

In addition, the top layer of water from the Black Sea has high surface current speeds, as high as 3.5-4 kn (Kokkini, 2014), a game changer that considerably raises the technical difficulty. A current this strong, for the less thalassic, has water moving at jogging speed, 4.6 mph, and it is not recommended for diving since according to a diving school..., your mask is fluttering and threatening to fly off, and your regulator begins to free-flow. Good swimmers, however, can compete in events like, the WORLD'S OLDEST SWIM in the annual 'Victory Day' Hellespont swimming race in Çanakkale, Turkey. Before traveling, though, swimmers are warned: They should be capable of swimming 4½ km in the open water and be comfortable swimming in choppy waters and currents prior to the start of the trip.

The city of Troy was a service station for traffic in and out of the Hellespont, as it was located on the south bank of the Aegean entrance. Because the strong currents and the afternoon winds are predominantly from the northwest, ships had to wait until the early morning before they could enter the Hellespont. Troy, nearby Sigeum, and the island of Tenedos became important waiting stations. Troy stands 17 miles from Çanakkale; approximately a 20-mile drive or a half-hour taxi ride for ten 2022 dollars.

Before examining the details of Xerxes' epic construction that withstood the Hellespont's untender mercies, let us give some thought to the faceless souls charged with building the bridges, men Herodotus refers to as, those who were appointed to the thankless honor.

The Engineers

To fully understand the challenge of building Xerxes' pontoon bridges over the Hellespont, one needs to look at the master builders to whom the king assigned the final task. They were the replacements. The previous team having met their demise after disappointing the Great King with the loss of the first pair of bridges to a storm. Xerxes was furious.

When Xerxes heard of this, he was very angry and commanded that the Hellespont be whipped with three hundred lashes, and a pair of fetters be thrown into the sea. I have even heard that he sent branders with them to brand the Hellespont. He commanded them while they whipped to utter words outlandish and presumptuous, “Bitter water, our master thus punishes you, because you did him wrong though he had done you none. Xerxes the king will pass over you, whether you want it or not; in accordance with justice no one offers you sacrifice, for you are a turbid and briny river.” He commanded that the sea receive these punishments and that the overseers of the bridge over the Hellespont be beheaded (Hdt. 7.35).

One can reasonable expect, therefore, some over-engineering in design and overzeal in execution from the team of replacement engineers, who on the way to the site probably had to walk by a crop of heads on spikes, those of their predecessors, as warning to not to screw the pooch this time. The excellent results achieved speak of a team acutely focused on doing a good job.

The Bridges

The location of the bridges that fits Herodotus' description is near the shortest crossing point, as shown in Figure 2, a slanted view of the modern site with an eye altitude of 1 km (0.62 mi). Allowing for the curvature, these bridges would have been about 2 km (1.24 mi) long.

Figure 2 -- Likely Location of the Bridges.

Herodotus provides a detail-rich high-tech description of how the bridges were constructed. It's as good a description one would get from a lay person about a complex engineering project. We are always left wanting for more details, at least to dispel the obvious problems that arise from the description. Thankfully, there are ways to make the narrative live to its best possibilities without having to contradict Herodotus, by filling a few of the blanks with facts we know to be true. This is how Herodotus describes the process.

They made the bridges as follows: in order to lighten the strain of the cables, they placed fifty-oared ships and triremes alongside each other, three hundred and sixty to bear the bridge nearest the Euxine sea, and three hundred and fourteen to bear the other; all lay obliquely to the line of the Pontus and parallel with the current of the Hellespont. After putting the ships together they let down very great anchors, both from the end of the ships on the Pontus side to hold fast against the winds blowing from within that sea, and from the other end, towards the west and the Aegean, to hold against the west and south winds. They left a narrow opening to sail through in the line of fifty-oared ships and triremes, that so whoever wanted to could sail by small craft to the Pontus or out of it. After doing this, they stretched the cables from the land, twisting them taut with wooden windlasses; they did not as before keep the two kinds apart, but assigned for each bridge two cables of flax and four of papyrus. All these had the same thickness and fine appearance, but the flaxen were heavier in proportion, for a cubit of them weighed a talent. When the strait was thus bridged, they sawed logs of wood to a length equal to the breadth of the floating supports, and laid them in order on the taut cables; after placing them together they then made them fast. After doing this, they carried brushwood onto the bridge; when this was all laid in order they heaped earth on it and stamped it down; then they made a fence on either side, so that the beasts of burden and horses not be frightened by the sight of the sea below them. (Hdt. 7.36)

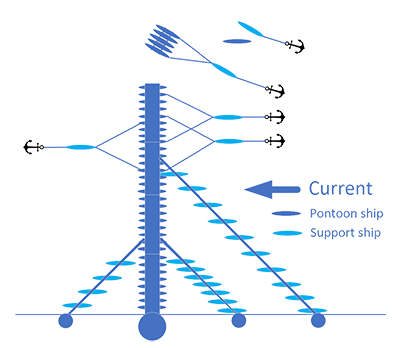

The sketch of the bridges in the title faithfully illustrates Herodotus description. I see two obvious ways of building the bridges, among possible others:

- Stretch cables between the shores and attach the pontoon ships to them.

- Anchor ships against the current, and attach one or more pontoon ships to them.

Did Persia have enough iron to make thousands of heavy anchors in the Hellespont bridges? It is what Herodotus suggests. Casting so many anchors dangling from ships side by side, would rapidly cause a Gordian knot of cables, probably causing the loss of many anchors. It also seems unfeasible, even before trying to figure out the physical forces involved, that cables 2 km long able to withstand the entire bridge could have been manufactured and deployed with the available technology. These cables would have to hold hundreds of hulls steady against 4 kn currents in one direction, and gale winds from either direction. No doubt there were able to manufactore stout cables, as Herodotus describes, to fix the ends of the bridges to the shore, but I doubt they extended all the way to the other shore.

I believe it is more feasible to proceed in this manner. After fastening a series of ships to the shore by means of stout cables, and attach more ships to those, additional support for the bridge comes from the sea bottom, by heavy anchors dropped on both sides of the bridge. As construction moves into deeper waters, bridge sections are added by this procedure, as shown in Figure 3. Support anchor-ships find solid anchorage in the bed of the strait along the crossing. A few pontoon ships attach to the each anchor-ship and hang in the current in line with the previous section and connect to it. A number of ships have ancillary roles supporting lateral attachment cables from the bridge to land bollards.

Figure 3 -- Bridge attachments and anchorings.

Herodotus implies that a combination of triremes and pentecosters were used as pontoons, but these ships had different height and a single bridge would use only one kind for a level support base. Or perhaps triremes were used solely as poontoons and pentercosters in ancillary roles. Or one bridge was supported by triremes and the other by pentecosters. It is unlikely that they were used together in the same bridge. None of this contradicts Herodotus, who unfortunatly gives no further details.

The Crossing of the Hellespont

The combatants and baggage train of Xerxes' army took seven days and nights crossing the bridges of the Hellespont, without pause. Suffices to say that working our the rate of traffic crossing the bridges, leaves ample margin for the entire host to cross over in this allotted time. Even at minimal efficiency bridges were wide enough to see everybody cross over in seven days and then some.